One trick that television series use, which I feel is totally unfair, is to draw an audience in by offering heroes who are noble characters then tearing them apart with substance abuse, sexual affairs, and utter failures of professional judgement.

I first noticed this when the hour-long nighttime soap operas hit the air in the late 1970s. In 2010 and 2011, one show did such poor planning and caring for the narrative arc that the production company had to reboot the series with a horrible plot device that, in my opinion, destroyed any credibility the story had left. In the end the plot line was in disarray, viewers didn’t know the good guys from the bad guys, and they stopped watching.

In my humble opinion, this act of drawing the audience in with a role model they are looking for then dashing the image of their hero is not being fair. Good writers, with any say in the matter, ought to resist writing what turns out to be a plot to Nowhere.

____

It’s rather obvious that any human will make decisions or be driven to participate in events they would have preferred not to have been involved with. It may be something simple like offending a fellow classmate or more serious like being coerced into a chain of criminal activities.

The fictional character’s history ought to reflect the dynamics we see in real life and, depending on the period your story’s timeline covers, the same character may be on one side of the moral line or the other. An author must be faithful to their characters’ position on the segment of the timeline they occupy. The character’s strengths and weaknesses then will be perceived according to the readers cultural ideals.

Has the hero/protagonist fallen in the past? Been reformed? What about the villain/antagonist? What in your readers’ minds will make them side with one or the other?

If you are going to write a story with a falling hero, or a redeemed villain, or even a villain with principals — be consistent in how your character reacts to challenges in plot!

In The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, Mark Twain invites the reader to follow the fictional town Hadleyburg. Here is where he picks up the story:

It was many years ago. Hadleyburg was the most honest and upright town in all the region round about. It had kept that reputation unsmirched during three generations, and was prouder of it than of any other of its possessions. It was so proud of it, and so anxious to insure its perpetuation, that it began to teach the principles of honest dealing to its babies in the cradle, and made the like teachings the staple of their culture thenceforward through all the years devoted to their education. Also, throughout the formative years temptations were kept out of the way of the young people, so that their honesty could have every chance to harden and solidify, and become a part of their very bone. The neighbouring towns were jealous of this honourable supremacy, and affected to sneer at Hadleyburg’s pride in it and call it vanity; but all the same they were obliged to acknowledge that Hadleyburg was in reality an incorruptible town; and if pressed they would also acknowledge that the mere fact that a young man hailed from Hadleyburg was all the recommendation he needed when he went forth from his natal town to seek for responsible employment.

But at last, in the drift of time, Hadleyburg had the ill luck to offend a passing stranger …

What a setup! It sounds like the whole town is going to be challenged! Whose side will you choose? The honest town or an offended stranger?

In this story, Twain offers a consistent image of the human condition. What compels the reader to continue through to the end? The thread of truth and the manner by which we arrive at the resolution.

Blurring the Line

An excellent example of blurring the distinction between hero and villain is the 1971 movie The Anderson Tapes. The premise is that a man, the protagonist Duke Anderson, is released from prison after serving a ten-year sentence and begins planning a new crime. As the story unfolds, the audience must decide who to root for: Anderson or the police. Because of the way in which the truth is revealed, viewers can choose one or the other and their choice is influenced to a greater degree by their internal sense of right and wrong rather than a matter of law or what they were taught to believe.

Capturing the Real World

Some years ago, I was talking with a World War II veteran while a television was running in the background when the story of the discovery of another Nazi in hiding broke into our conversation. Of the big names, Klaus Barbi and Adolf Eichmann had already been captured, leaving few the likes of Josef Mengele still at large.

The veteran listened carefully to the summary of the man’s history since the war and said, “They ought to let him stay where he is.”

Sitting across from me was a man who gave years of his life fighting the very ideals the accused Nazi represented. When pressed, the veteran said, (paraphrasing) “The war’s over. He did what he had to do. He’s got a job, raised a family, and been a good citizen since then. Only one in ten were hardcore Nazis. Everyone else went along and could have been killed if they didn’t. He’s shown he’s not one of the bad ones. ”

Was the veteran expressing simple Christianity, being magnanimous, or did he recognize that, if the tables were turned and Germany had won, he could be the one being arrested?

Yehiel Dinur and Adolf Eichmann

Yehiel Dinur was a witness at the trial of Adolf Eichmann. There was a news cast at the time which showed Dinur collapse and sob uncontrollably while giving testimony.

I was about 11 years old. My father was outraged. Why after all this man, Dinur , went through did the court make him retell the horrors of captivity? Why did the television station air this terrible footage and bring back the memory of a war Dinur, my father, and others would rather leave behind?

As an adult, while watching a 60 Minutes interview Mike Wallace did with Dinur, I learned it wasn’t the horror of Hitler’s concentration camps that caused Dinur’s reaction.

… Dinur explained to Wallace, all at once he realized Eichmann was not the god-like officer who had sent so many to their deaths. This Eichmann was an ordinary man.

“I was afraid about myself,” said Dinur. “… I saw that I am capable to do this. I am … exactly like he.”

Quoted from The Measure of a Man.

… and of Hitler?

Was he ever good? Many worshiped him. Was he principled in his evil? Consistent in his thoughts and actions?

Sadly, it appears from recently-released documentaries that except for brief opportunities, his life was doomed almost from the start. Abused and neglected as a child, caught up in World War I, the hyper-inflationary period that followed, and put in a position that allowed his twisted sense of reality to manifest — he for some unknown reason targeted one of the few groups of people who consistently helped him as a young man — the Jews.

If I were going to write about an ultimate evil character, it would be hard to do better than to map my character’s life to Adolph Hitler’s path. I wouldn’t have to describe every detail to my audience. If I did my job right, it wouldn’t matter.

Bottom Line?

Be consistent. Be fair. Letting your audience decide whether the characters are good or bad is fine. And if you’re writing for me, don’t mess with the heroes — the world needs more of them. Kill them if you must, but let them die with honor. Let their lives mean something!

– Jeffrey A. Limpert

__________________

References:

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Anderson Tapes

The Measure of a Man

Image Information:

Protected

By h.koppdelaney (Hartwig HKD)

https://secure.flickr.com/photos/h-k-d/4040360452/

____

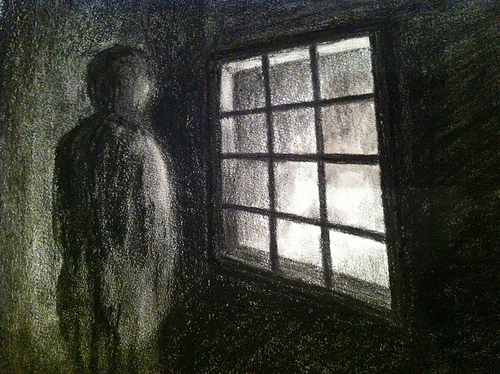

Isolation

By Camillaen (Camilla)

https://secure.flickr.com/photos/camillaen/6325164180/

Amazon – Unfolding: Awakening

Amazon – Unfolding: Awakening